Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 5281 3635

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 24177

- CEN 19 (Morris)

- Duncroisk 2 Carving (Canmore)

- Tirai Wall Carving

- Tullich (Morris)

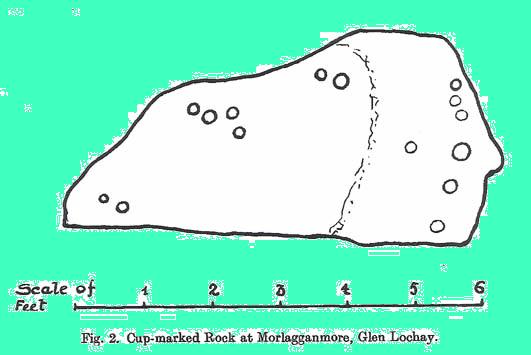

Go thru Killin and, just past the Bridge of Lochay hotel, take the tiny road on your left. Go down here for 3 miles till you pass the gorgeous Stag Cottage (with its superb cup-and-rings in the field across the road) for another 300 yards, past Duncroisk Farmhouse set back on your right, then over the small river bridge. Just over the bridge there’s a gate on your left. Go thru this and up the track until you get to another large gate. Go thru this, then walk immediately left where you’ll notice a large-ish boulder sat on the nearby slope ahead of you in a part of some very old walling. That’s your target!

Archaeology & History

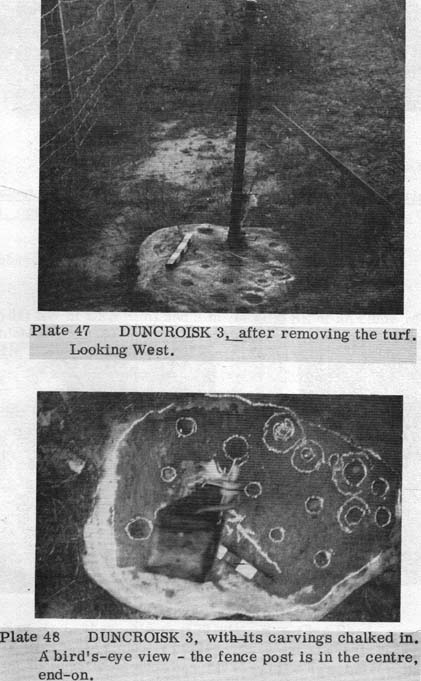

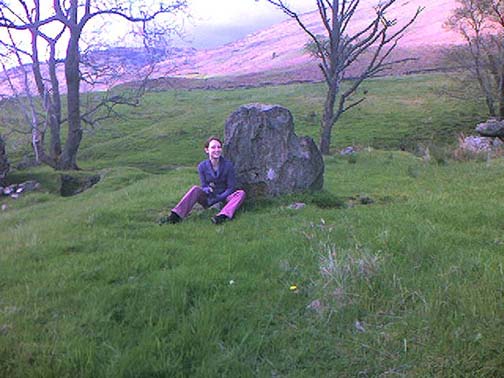

The title of this carving is slightly misleading, as the stone concerned is about 50 yards west of the fast-running burn. But it’s pretty easy to locate. When we visited the stone recently, as the photos show, the rock was all-but covered in a beautiful patchwork of lichen and moss, inhibiting the visibility of a quite impressive carving. But we have to let this be.

The carved rock plays an important part in a line of ancient prehistoric walling, which looks Iron Age in nature, but without an excavation we’ll not know for certain. The walling is quite extensive and is an integral part of the extended derelict village of Tirai, with its standing stones and other monuments. This begs the questions: was the carving executed before or after the walling was created? Was the stone carved in traditional neolithic/Bronze Age periods and later accommodated into the walling?

Even in the grey overcast light of a winter’s day when we first visited here, many cups were clearly visible on the rock’s surface, but they were difficult to contextualize in terms of artificial and natural aspects of the stone. Later visits here at the end of Spring enabled a much better assessment — though capturing the surrounding “rings” proved difficult. The carving is shown highlighted on Ron Morris’ (1981) map of the cluster of Duncroisk carvings, and described as a:

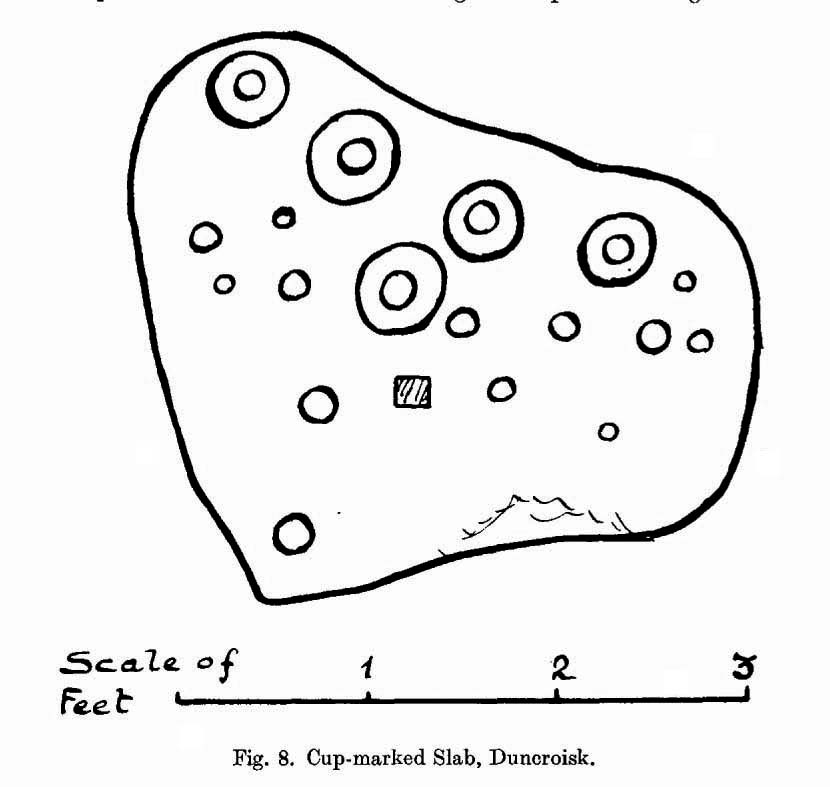

“domed schist boulder, 2½m by 2m, 1¼m high (8ft x 6ft x 4ft). On its top, mostly where sloping…are: 2, and possibly 3, cups-and-one-ring, much weathered and only visible when wet in very low sun, probably un-gapped, and at least 32 cups. Diameters up to 17cm (6½in) and depths up to 1cm.”

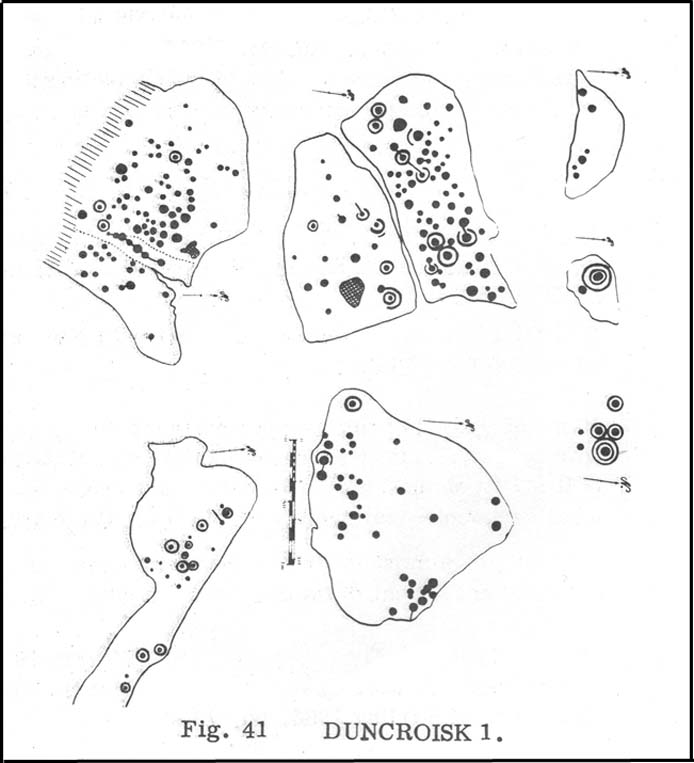

But this is only half the story. Despite what Mr Morris and the more recent Canmore records tell us about this carving, there are in fact at least 52 cups on the surface of the rock, at least two of which have definite ring-like forms around them. The largest of the cups has linear features around a large section of it, but to ascribe these elements as ‘rings’ is also stretching it a bit — as one of the photos here clearly shows. The ‘ring’ consists more of two separate straight lines with curvaceous ends: more like a right-angled carving with a swerve than any traditional ring. It’s a quite unique feature by the look of things.

The majority of the carved cups and lines occur on the eastern side of the boulder, with only a few singular cups almost fading their way onto its western sloping sides. And of primary visual interest are the swirl of cups that surround two small cups at the ESE corner of the rock. These give the impression of running into another swirl of cups that hedge their ways around the edges of the largest cup-and-right-angled-lines, until bending back up and along the southern-side of the stone. This possibly deliberate sequence of cups then continues in roughly the same form back upwards to near the top-middle of the rock and onto a complete cup-and-ring. Just above the top of this runs a short pecked line just detached from the cup-and-ring, but of obvious mythic relevance in the story which this carving once told.

It’s an absolutely fascinating carving which gives the distinct impression of narrating a myth of journeying, by either a person, tribes or ancestral beings. Of course we’ll probably never know for sure what story it once told; but its tale may have been known by the people of the once proud village of Tirai which was only destroyed a couple of centuries ago, along whose fallen walls this great stone still rests within…

And finally, for those students exploring the potential relationship that cup-and-rings may have with water: please note that in wet conditions, a spring of water emerges right underneath the very base of this large rock.

…to be continued…

References:

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR 86: Oxford 1981.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1979.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian