Cairn (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 782 929

Archaeology & History

At the bottom of the ridge from the (supposedly) singular King’s Park cup-and-ring stone,” in a sand-pit adjoining Douglas Terrace,” we could once find the remains of a now lost prehistoric tomb. First described in the Stirling Natural History Society’s Transactions in 1907, the Scottish Royal Commission lads (1963) told us that, “an urn from this cist was taken to the Smith Institue, Stirling, in a broken condition.” Anymore information about this site, or images of the fragmented urn, would be hugely appreciated.

It does seem very probable that the King’s Park cup-and-ring stone at the top of the ridge from here did relate to local neolithic or Bronze Age burial sites, as I suspected. It’s highly likely that other carvings were (are?) hidden beneath, or round the edges of this Douglas Terrace and Kings Park region, as I suggested a few months ago. It’s imperative that archaeologists in the district pay attention to this area before giving the go-ahead of any further landscape destruction.

References:

- Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Birkhill House, Cambusbarron, Stirlingshire

Cairns (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 780 926

Archaeology & History

In times past, there were at least two prehistoric tombs in land either side of old Birkhill House, now covered by the M9 motorway. The Scottish Royal Commission lads described the first as being “in the garden of Birkhill House,” continuing:

“This cist contained bones and an urn which measured 5in in height and 6in in diameter, and was ornamented with zigzag lines.”

They think, from its description, that “it may have been a food vessel.” There were also the remains of another tomb to be found in “rising ground to the west side of” Birkhill House. Both of these finds were first described in the local Transactions of the Stirling Natural History and Antiquarian Society in 1880. It seems that little else is known about them. (Thanx again to Paddybhoy for prodding my attention here.)

References:

- Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Coneypark Nursery, Cambusbarron, Stirlingshire

Cairns (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 783 926

Archaeology & History

At least two old tombs that could once be seen here are long-gone by all accounts. They could be found 200 yards south of the remaining King’s Park cup-and-ring stone. The first was described by the Royal Commission lads (1963) as a well-defined cist, “situated within a gravel mound and (it) contained a skeleton.” Another tomb site was described a few years later:

“A second short cist was found just within the cairn material 3m SE x E from cist no.1. It consisted of a capstone set on built-up side walls, the bottom courses being five slabs on edge. The internal measurements were 64cm long and 48cm wide and 60cm deep. This second cist was orientied NE-SW with its floor made of small pebbles on which lay a late incised beaker and a small piece of human skull.”

References:

- Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Thompson, J.K., “Coneypark: Bronze Age Cairn,” in Discovery & Excavation in Scotland, 1972.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

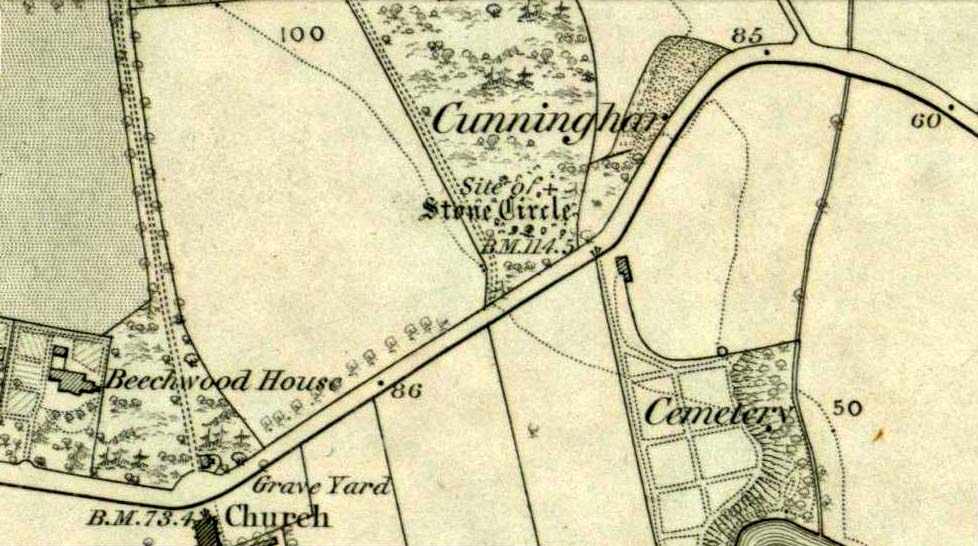

Cunninghar, Tillicoultry, Clackmannanshire

Stone Circle (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 9256 9709

Also Known as:

- Druidical Temple

Archaeology & History

A stone circle was once to be found on the elevated piece of ground above the north-side of the main road between Tillicoultry and Dollar, but it was sadly destroyed sometime in the 19th century. Listed in Burl’s (2000) magnum opus, we have very little information about the place; though an account of the site was described in the Scottish Royal Commission report (1933) which told that a —

“Stone circle, measuring about 60 feet in diameter, once stood here but was completely removed many years ago, when the stones, which are said to have been 5½ feet in average height, were taken to cover a built drain at Tillicoultry House”!

Unbelievable! Any decent local folk nearby wanna find out where this drain is, see if the stones are visible (though I doubt they are), so we can plan to uproot it and move the stones back somewhere nearby. There are a few decent spots on the slopes above where it would look good!

When visited by researchers in the 1890s, parts of an embankment which surrounded the destroyed circle were still visible. Also, indicating there was some ritual funerary nature to the site, a local teacher called Mr Christie found the remains of an ornamented urn protruding through the ground next to where one of the monoliths had stood. Unfortunately in his attempts to remove the urn, much of it crumbled away.

Further examinations thereafter found that a burial was (seemingly) beneath the centre of the circle; and excavations here found that a covering stone of the tomb was covered in intricate cup-and-ring designs (see the Tillicoultry House Carving for further details). Other prehistoric remains were found a little further up the hill from here.

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR 86: Oxford 1981.

- Robertson, R., ‘Notice of the Discovery of a Stone Cist and Urns at the Cuninghar, Tillicoultry…’, in PSAS 29, 1895.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Fife, Kinross and Clackmannan, HMSO: Edinburgh 1933.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Gariob Cottage, Achnamara, Knapdale, Argyll

Cairn: OS Grid References – NR 7801 8910

From Lochgilphead go north up the A816 for just over a mile, turning left going through Cairnbaan to Bellanoch, where the road bends left up the B8025 into the trees. Keep along here for a mile and when the small road appears on your left, follow it for just over a mile till you see the cottage on the roadside with the loch at tha far end of the garden. There’s a small path besides the cottage. Walk along here for 100 yards until you see the small cairn on your left.

Archaeology & History

This is a beautiful quite place with only a small pile of stones here, about 100 yards west of Gariob Cottage on the ridge overlooking Loch Sween. The remains of the cairn here are about 20 feet across (or were when I last came here nearly 20 years ago!). Excavations here in 1977 and 1978 found a small cist split into 2 sections, just off-centre, aligned northwest. The lower part of the cist was filled with small stones and charcoal; whlst the larger section had the same with additional quartz stones in it.

References:

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historic Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – volume 6, HMSO: Edinburgh 1988.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

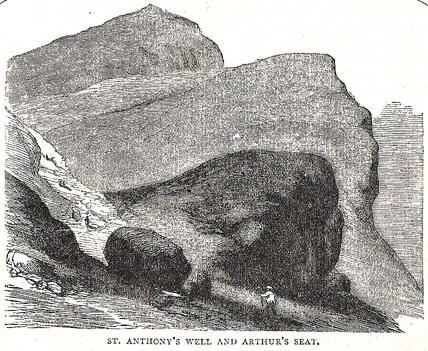

St. Anthony’s Well, Edinburgh, Midlothian

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NT 27522 73653

Also known as:

- Canmore ID 52448

- St. Anton’s Well

Not too difficult to find really. Get to the northern part of the road which encircles Arthur’s Seat and when you get to St. Margaret’s Loch (near St. Margaret’s Well), look up the slopes where you see the remains of St. Anthony’s Chapel. You need to head up the footpath here and you’ll get to a large-ish ovoid boulder, with a small circular trough into which the waters run (the drawing of the place here, with the rock in the lower-left, just in front of the fella walking towards it, is just right!). You’re here!

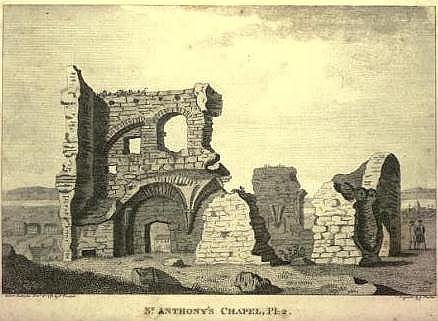

Archaeology & History

Tradition tells that the remains of St. Anthony’s Chapel was built on the northern ridge by Arthur’s Seat, “mainly for guardianship of the holy well named after the saint” — which sounds rather like the christianization story of a heathen site. Francis Grose (1797) told that “this situation was undoubtedly chosen with an intention of attracting the notice of seamen coming up that Frith; who, in cases of danger, might be induced to make vows to its tutelar saint.” If this was the case, it sounds even more like a site that had prior heathen associations. Grose also told us that just a short distance from the chapel, were the remains of an old hermitage:

“It was partly of masonry worked upon the natural rock. At the east end there are still two niches remaining; in one of which formerly stood a skull, a book, an hour-glass, and a lamp, which, with a mat for a bed, made the general furniture of the hermitage.”

I like the sound of the place! Just up my street! Little other archaeological info has emerged from this tiny spot — but the healing waters of the well would obviously have been of importance to our indigenous inhabitants (anyone who wants to think otherwise is simply a bit dim!) as there is a wealth of archaeological sites and relics all round Arthur’s Seat.

Folklore

A number of writers have described this old well, which has sun-lore, healing properties, and Beltane rites surrounding its past. Local people of all social classes frequented this ancient spring, particularly on that most favoured of heathen days, Beltane. The site was of considerable mythic importance with a certain order about it. As Hone (1839) said:

“…the poorer classes in Edinburgh poured forth at daybreak from street and lane to assemble on Arthur’s Seat to see the sun rise on May-morning. Bagpipes and other musical intruments enlivened the scene, nor were refreshments forgotten. About six o’ clock a crowd of citizens of the wealthier class made their appearance, while the majority of the first-comers returned to the town. At nine o’ clock the hill was practically deserted.”

Another early account describing St. Anthony’s Well is from an article in the great PSAS journal of 1883. Here, J.R. Walker wrote:

To an incident which showed that the faith and belief in the healing virtues of the wells is still strong, the writer was but a few months ago an eye-witness. While walking in the Queen’s Park about sunset, I casually passed St. Anthony’s Well, and had my attention attracted by the number of people about it, all simply quenching their thirst, some possibly with a dim idea that they would reap some benefit from the draught. Standing a little apart, however, and evidently patiently waiting a favourable moment to present itself for their purpose, was a group of four. Feeling somewhat curious as to their intention, I quietly kept myself in the back ground, and by and by was rewarded. The crowd departed, and the group came forward, consisting of two old women, a younger woman of about thirty, and a pale, sickly-looking girl — a child of three or four years old. Producing cups from their pockets, the old women dipped them in the pool, filled them, and drank the contents. A full cup was then presented to the younger woman, and another to the child. Then one of the old women produced a long linen bandage, dipped it in the water, wrung it, dipped it in again, and then wound it round the child’s head, covering the eyes, the youngest woman, evidently the mother of the child, carefully observing the operation, and weeping gently all the time. The other old woman not engaged in this work was carefully filling a clear flat glass bottle with the water, evidently for future use. Then, after the principal operators had looked at each other with an earnest and half solemn sort of look, the party wended its way carefully down the hill

Earlier still we find more lore of the place in Wilson’s Edinburgh [1848] where he told:

“The ancient Hermitage and Chapel of St. Anthony, underneath the hangings of Arthur’s Seat, are velieved to have formed a dependency of the preceptory at Leith, and to have been placed there, to catch the seaman’s eyes as he entered the Firth, or departed on some long and perilous voyage; when his voews and offerings would be most freely made to the patron saint, and the hermit who ministered at his altar. No record, however, now remains to add to the tradition of its dedication to St. Anthony; but the silver stream, celebrated in the plaintive old song, ‘O waly, waly, up yon bank,’ still wells clearly forth at the foot of the rock, filling the little basin of St. Anthony’s Well, and rippling pleasantly through the long grass into the lower valley.”

Votive offerings made here eventually turned the waters into a simply wishing well for incomers, even in Victorian times (oh how the locals must have hated such trangression…). The great Scottish holy wells writer J.M. MacKinlay (1893) told in his day the tale of,

“a little girl from Aberdeenshire, when on a visit to Edinburgh, made trial of the sacred spring. She was cautioned not to tell anyone what her wish was, else the charm would have no effect. On her return home however, her eagerness to know whether the wish had…been fulfilled, quite overcame her ability to keep the secret. Her first words were, ‘Has the pony come?’ St. Anthony must have been in good humour with the child, for he provided the pony, thus evidently condoning the breach of silence in deference to her youth.”

In the middle of the 20th century, the great folklorist F.M. MacNeill (1959) wrote:

“Even in Edinburgh, little bands of the faithful may be seen making their way through the King’s Park to Arthur’s Seat, and, as in the eighteenth century:

On May-Day, in a fairy ring,

We’ve seen them round St. Anton’s spring,

Frae grass the caller dew-drops wring,

To weet their een,

And water clear as crystal spring,

To synd them clean.”

And when Ruth and Frank Morris (1982) got round to their excellent survey, they found that this old well was still being used “by youths and maidens, who come to wash their faces with the dew on May Day mornings, a wish at St. Anthony’s being a part of the ritual.” But this final remark may have the simple prosaic coincidence of them observing people like I, when younger, who frolicked with girlfriends around May morning, in the grasses near the old well — though at the time I knew nothing about the old sacred waters on the slopes just above us!

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Edinburgh, TNA: Alva 2017.

- Grose, Francis, The Antiquities of Scotland – volume 1, Hooper & Wigstead: London 1797.

- Hone, William, The Every-Day Book and Table-Book, Thomas Tegg: London 1839.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- McNeill, F. Marian, The Silver Bough – volume 2, William McLellan: Glasgow 1959.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Walker, J. Russel, “‘Holy Wells’ in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol.17 (New Series, volume 5), 1883.

- Wilson, Daniel, Memorials of Edinburgh in Olden Times, Hugh Paton: Edinburgh 1848.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

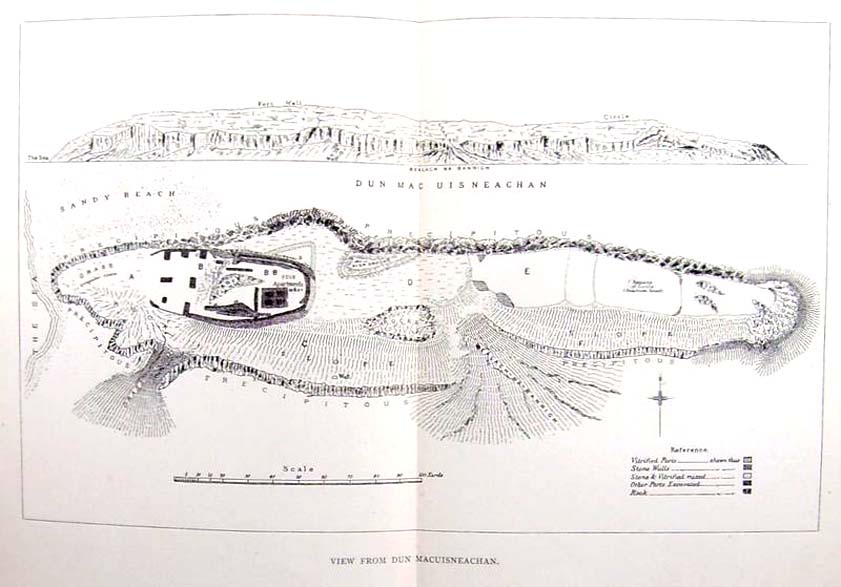

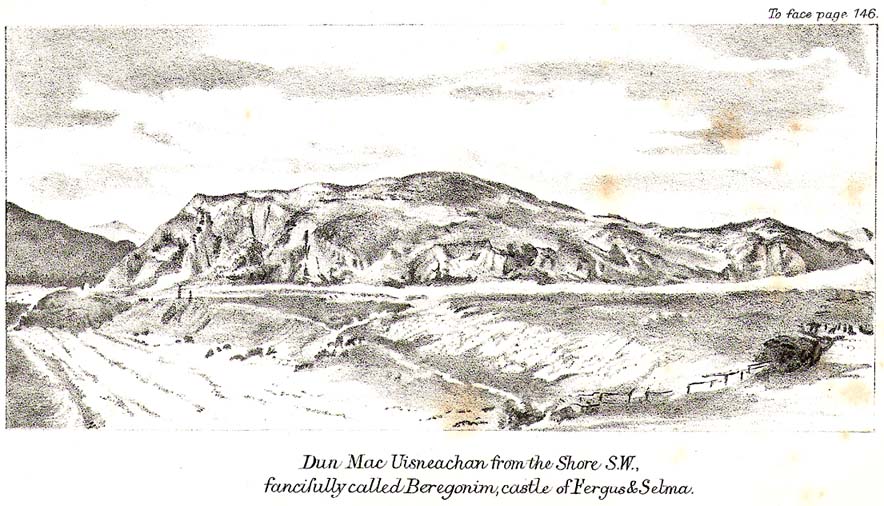

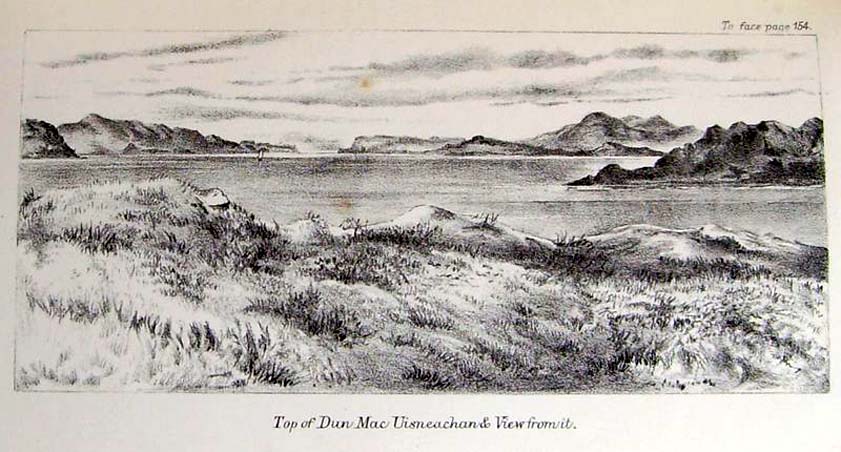

Dun Mac Sniachan, Benderloch, Argyll

Hillfort: OS Grid Reference – NM 9032 3822

Also Known as:

- Dun mac Uisneachan

- Dun Uisnach

- Beregonium

Archaeology & History

This is a fine-looking monument amidst a fine piece of landscape! The site was constructed over various centuries, beginning in the Iron Age, with the earliest parts being the traces of walling on the outer edges. This first section of the fort “measures about 245m in length by a maximum of 50m in width internally,” and much of it can still be traced all along the full length and breath of the geological ridge upon which it sits. However, the timber-laced walls that stood all round the edges have, obviously, all but disintegrated. This earlier part of the fort, wrote Richard Feacham (1977),

“was superceded by a small subrectangular, now vitrified fort, about 170 feet long by 60 feet wide, and by a circular and probably vitrified dun measuring about 60 feet in diameter.”

There was ample water supply for the people who may have lived on this ridged fortress, as there is still a fresh water spring on the southeast edge of the hill. And it seems pretty obvious that this fort was occupied for some considerable time into the Common Era, as material remains found amidst excavation work here at the end of the 19th century, “including metalwork of Roman date…suggests an occupation in the early first millenium AD.” (Harding 1997)

Folklore

The folklore and legends of this site (aswell as the surrounding district) are considerable, and for now I must refrain from writing all there is (it’d take me ages!). Needless to say, R. Angus Smith’s (1885) fine old history and folklore work is the source of much material. Smith told us that,

“There are many stories about it. It has been called the beginning of the kingdom of Scotland, the palace of a long race of kings; also the Halls of Selma, in which Fingal lived; the stately capital of of a Queen Hynde, having towers and halls and much civilization, with a christianity before Ireland; whilst it has also been considered to be that which the native name implies, simply the fort of the sons of Uisnach, who came from Ireland, and whose names are found all over the district, and who in the legend are reported to have come to a wild part of Alban.”

References:

- Feacham, Richard, Guide to Prehistoric Scotland, Batsford: London 1977.

- Harding, D.W., “Forts, Duns, Brochs and Crannogs,” in The Archaeology of Argyll (edited by Graham Ritchie[Edinburgh University Press 1997]).

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Argyll- volume 2, HMSO: 1974.

- Smith, R. Angus, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach, Alexander Gardner: London & Paisley 1885.

Links:

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Druimyeonbeg, Isle of Gigha, Argyll

Cist (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NR 6463 4958

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

An old stone-lined burial cist could once be seen in this locale: reported in 1953 to have been “discovered in the southwest corner of a field south of Druimyeonbeg farmhouse.” When it was uncovered by the farmer, the covering capstone was missing. Any relics that may have been there were destroyed and there’s now no trace of anything.

References:

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 1: Kintyre, Glasgow 1971.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Clach na h-ealea, Clachan, Lismore, Argyll

Legendary Stone: OS Grid Reference – NM 8609 4342

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 23090

- Clach na h-eala

- Stone of the Swan

- Swan Stone

Archaeology & History

Although the lads at the Scottish Royal Commission (1974) initially described this site as a ‘Standing Stone’, it is in fact,

“an erratic boulder of granite roughly shaped in the form of a cross… It measures 0.8m in height, 0.6m in width at base, and 0.4m in width at the top…(and) the stone is supposed to have marked a boundary.”

The site was evidently of some mythic importance, as the great Cathedral of St. Moluag was built next to the stone — unless the giant cairn of Cnoc Aingil, 500 yards away, was to blame. A holy well of this saint’s name (an obvious heathen site beforehand) is also nearby.

Folklore

Although this stone was dedicated to swans, I’ve not found the story behind the name. There were no buried swans here, but local tradition told that this old boulder could give sanctuary to anyone who touched it, or ran round it sunwise. The Hebridean folklorist Otta Swire (1964) told that,

“anyone who claimed such sanctuary had his case considered by ‘the Elders.’ If they considered his plea justified, they ‘came out and walked sun-wise round the Swan Stone.’ If they did not approve of his right to sanctuary, they walked round it anti-clockwise and the man was then given over, not to his enemies, but ‘to Authority’ to be tried.”

This old tradition derives from well known pre-christian rites. Swire also reported that even in the 1960s here, “at funerals the coffin is always carried round the grave sun-wise before being laid in it.” An old cross placed in the Field of the Cross next to the stone was an attempt to tease folk away from heathen rites of the stone, but failed.

References:

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – volume 2: Lorn, RCAHMS: Edinburgh 1974.

- Swire, O.F., The Inner Hebrides and their Legends, Collins: London 1964.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

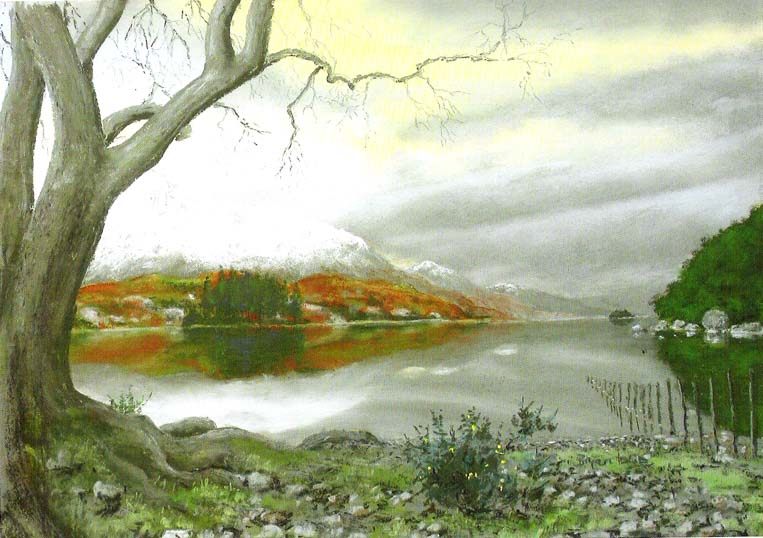

Holy Well of Isle Maree, Loch Maree, Ross & Cromarty

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NG 9310 7236

Also known as:

- Canmore ID 12049

- Mourie

- St. Maelrubha’s Well

We were up here again in July 2009, but I’ve still not been across onto the island itself — just stared from the lochside, dying to swim across and spend a night or three alone on the island amidst this legendary landscape. Basically, get to Talladale on the A832 (halfway between Gairloch and Kinlochewe), then walk up to the loch-side to your right (east) for a mile till you reach the small wooded outcrop. Look north, betwixt the two isles and its the one in the middle with the Crag of the Bull and Maire’s Cairn rising up the mountain face behind. But you can reach it via a boat trip from one of the local harbours. Staying there overnight however, would seem more troublesome. It seems that a winter visit seems best!

Folklore

This ‘holy well’ has a prodigious occult history which, sez my nose, is still maintained by one or two old Highland folk up here. This small island (one of many in this long loch) was the Isle of the Druids in old days: legend telling it to be the teaching ground of these shady priests. Even the Iona druids came here. The main relics on on the island are the old holy well, accompanied by an old legendary tree into which all local people flocked and wedged coins at least once in their life. This devotional rite eventually took its toll, with so many of the coins covering the old tree with metallic scales to a height of nine feet, eventually killing it.

The well itself was said to cure insanity — no doubt the remedial quality given to the waters after neophyte druids had spent many days of ritual solitude here, eventually sipping its life-giving fluid to revive them from their ordeal.

It eventually became sanctified by the Church: legend saying it was St. Maelrubha (the same dood who turned the healthy Applecross heathens into church-goers) who was the guilty party. Indeed, the name Maree itself, was proclaimed as deriving from this old saint, though local lore tells it to derive from the pagan ‘ane god Mourie.’

Elizabeth Sutherland (1985) reported that remains of the sacred tree were still visible. It is also said that no-one makes ritual commemmoration here anymore. Hmmmm… don’t always believe what you read.

In the 18th century, when Thomas Pennant visited this sacred well, he described that,

“in the midst is a circular dike of stones… I expect the dike to have originally been druidical, and that the ancient superstition of paganism had been taken up by the saint (Maelrubha) as the readiest method of making a conquest over the minds of the inhabitants.”

References:

- Dixon, John, Gairloch in North-west Ross-Shire, Co-op: Edinburgh 1886.

- MacKenzie, Kenneth C., Loch Maree: The Jewel in the Crown, privately printed 2002.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Pennant, Thomas, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides, MDCCLXXII, John Monk: Chester 1774.

- Polson, Alexander, Gairloch, George Souter: Dingwall 1920.

- Sutherland, Elizabeth, Ravens and Black Rain, Constable: London 1985.

- Watson, W.J., Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty, Northern Counties Printing: Inverness 1904.

* This beautiful painting is one of many done by local artist, Bryan Islip. It is taken from his 2010 Calendar, Scotland’s Wester Ross, and is available direct from him. If you’d like to know more, or want copies of his calendar or other artworks, email him at: pico555@btopenworld.com – or check his website at www.picturesandpoems.co.uk

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Painting © Bryan Islip