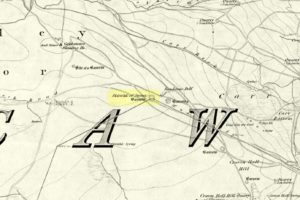

Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – SE 881 637

Also Known as:

- Towthorpe Barrow 1

Getting Here

The faded remains of this old burial mound can vaguely be seen just off the right-hand (east) side of the B1248, across the road from the track which leads down to Burdale North Wold farmhouse, between Fimber and Wharram-le-Street.

Archaeology & History

Known as Towthorpe Barrow No.1 in the Mortimer survey (1905), there are a number of prehistoric tombs and other remains close to this site (which will be described on TNA as time goes by). Some of you might think the lengthy description here a little unworthy, but I believe the extensive archaeological notes on this site by an archaeological legend, J.R. Mortimer, is a good indicator of the dedication and interest to which he gave each and every tomb that he opened (this’ll be the first of many). His slightly edited account told:

“This mound is situated near the centre of the (Towthorpe) group, close to High Towthorpe. Here the green lane…is crossed by the high road from Malton (B1248), through Wharram-le-Street… Part of this road, for some distance south and north of the barrow, is called ‘High Street’ by the old inhabitants of the neighbourhood…

“On 4 May, 1863, the writer, with the assistance of R. Mortimer and two workmen, commenced to open this mound. It was the first British barrow he had the pleasure of examining. A trench 10 feet wide was cut across its centre from the northern to the southern margin…

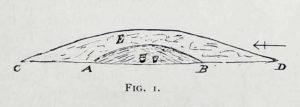

“The upper portion E, to a depth of 16 inches, consisted chiefly of the surface soil of the neighbourhood, the bottom part of which was reddened as if by the action of fire. Close below this was a stratum of wood and ashes and other dark matter, 2-3 inches in thickness; and then a lenticular bed of tough drab-coloured clay, 29 feet in diameter, and 12-14 inches thick in the centre, gradually thinning towards the circumference. The upper part of this bed of clay, which was in contact with the stratum of wood ashes, was reddened by fire; its under surface had a similar appearance and rested upon what seemed to be a second stratum of burnt and decayed matter, 2-3 inches in thickness, similar to that already described. The clay forming this lenticular bed contained numerous small fragments of grey flint, characteristic of the chalk of the neighbourhood. It must have been obtained from one of the valley bottoms (either Burdale, Wharram-le-Street or Duggleby), in which are exposures of the Kimeridge clay. In these places, angular pieces of flint and chalk crumble from the hillside, and mix with the clay, imparting a greyish colour to it. This is especially the case at Burdale, where there is a fine spring at the base of the chalk, and a small pond resting on the Kimeridge; and it is probably from this place that most of the clay for the construction of this barrow was obtained. It is not easy to explain the method by which the clay was transported, but several tons had evidently been used in this case. Many other instances in which material from a distance has been used in the erection of the barrows of this neighbourhood are recorded in (the Yorkshire Wolds).

“In the centre of the mound, at the base of the lenticular bed of clay and below the ashes (which probably represent the residue of a funeral pyre) stood two food vases, close together, and near to these, decayed bones (the remains of a human body) and a chipped flint. The smaller and more ornamented vase was situated to the south of its fellow. It measures 4.5 inches in neight, 5.5. inches in diameter at the top, and about the same across the shoulders. The ornamentation had been impressed on the plastic clay by a thin square-ended tool, about half-an-inch in length, which showed in the impression of a fine notched structure, and was equally divided into ten ridges about the size of the indentations on the milled edge of a shilling, and almost as truly cut. In the lower groove which runs round the vase are four pierced projections.

“The other vase is about 5 inches high and about 6 inches in diameter at the top and across the shoulders. Three encircling lines of short vertical cuts, rudely and apparently hastily made, previous to baking the vase, represent its entire ornamentation.

“During the excavation we collected from the material of the mound a dozen hand-struck flint flakes of various sizes, and a small splinter from the cutting-edge of a green-stone celt.”

Mr Mortimer returned to do further excavations here on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day in 1865, with the hope of finding more — but apart from a finely-cut knife made of black flint, nothing else was located. This was the first of Mortimer’s hundreds of diggings into the tombs and dykes of East and North Yorkshire.

References:

- Marsden, Barry M., The Early Barrow Diggers, Tempus: Stroud 1999.

- Mortimer, J.R., Forty Years Researches in British and Saxon Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire, A. Brown: London 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian