Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 85494 88272

Also Known as:

-

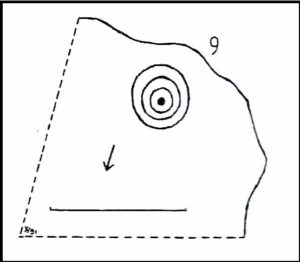

Castleton 9 (van Hoek)

Getting Here

If you’re travelling from Stirling or Bannockburn, take the B9124 east to Cowie (and past it) for 3¾ miles (6km), turning left at the small crossroads; or if you’re coming from Airth, the same B9124 road west for just about 3 miles, turning right at the same minor crossroads up the long straight road. Drive to the dead-end of the road and park up, then walk back up the road 350 yards to the small copse of trees on your left. Therein, some 50 yards or so, zigzag about!

Archaeology & History

Petroglyphs can be troublesome things at the best of time: not only in their ever-elusive root meanings, but even their appearance is troublesome! This example to the east of Cowie in the incredible Castleton complex is one such case. It is undoubtedly a multi-period carving, probably first started in the neolithic period, added onto in the Bronze Age, and maybe even finished in the early christian period. You’ll see why!

It’s been described several times in the past, with Maarten van Hoek (1996) telling how it was rediscovered,

“by Mrs Margaret Morris in 1986 in the birch-coppice at Castleton Wood. A fragment of outcrop rock with a distinct cup-and-three-rings, rather oval-shaped like others in the area.”

But as our own team found out, there’s more to it than that. Like many of the Castleton carvings, vital elements have been missed in the previous archaeological assessments. But it’s an easy thing to do. The carved design here almost ebbs and flows with daylight, shadows, changes in weather, bringing out what aboriginal and traditional peoples have always told us about rock itself, i.e., it’s alive, with qualities and virtues that can and do befuddle even that great domain of ‘objectivity’—itself an emergent construct of an entirely subjective creature (humans). But that’s what petroglyphs do!—whether they are part of a living tradition, or lost in our striving modernity, exhibiting once more that implicit terrain of animism. And this carving exemplifies it very clearly.

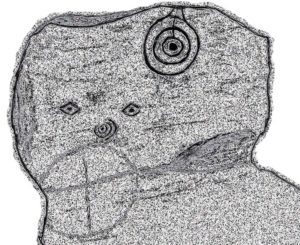

The primary visual design is the odd triple-ring, which isn’t quite as clear-cut as the earlier descriptions would have you think. In the drawing below by van Hoek (1996), three complete elliptical ‘rings’ are shown; whereas on its northern edge where the outer ring is closest to the rock edge, we find that the ‘ring’ has carved lines that run off and down the slope of the stone towards ground-level. It also seems that from the inner second-ring, a natural scar in the rock has been heightened by pecking, creating an artificial carved line running from near the centre and ‘out’ of the three rings. You can make this out in the accompanying photo, above.

Additionally we found two very faint carved ‘eyes’ or trapezoids pecked onto the stone, obviously at a much earlier date than the notable triple-ring—which could almost be modern! They would no doubt have excited the old archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford (1957), whose curious theory of petroglyphs was that they were images of some sort of Eye Goddess. Archaeo’s can come out with some strange ideas sometimes…

Fainter still was another triple-ring—albeit incomplete—with what appears to be a very small central cup-mark, just below and between the two ‘eyes’. It was first noticed by Paul Hornby when he was playing with the contrast settings on his camera, in the hope of getting clearer photos of any missing elements.

“Can you see this?” he asked. And although very faint indeed (on most days you can’t see it at all), it’s undoubtedly there: another multiple-ringer all but lost by the erosion of countless centuries, and older still than the ‘eyes’ above it. In all the photos we took of this stone, from different angles in different weathers (about 100 in all), this very faint triple-ring can only be seen on a handful of images. But it’s definitely there and you can see it faintly in the attached image (right) to the bottom-left.

A final note has to be made of a possible unfinished, large circular section with a cross carved into the natural feature of the stone, first noticed by Lisa Samson. It’s uncertain whether this has been touched by human hands (are there any geologists reading?), but it’s something that we’re noticing increasingly at more and more petroglyph sites. They’re not common, but it has to be said that we found two more man-made ‘crosses’ attached to multiple cup-and-rings near Killin just a few weeks ago. Also, folklore tells us that not far from this Castleton cluster, a christian hermit once lived….

References:

- Crawford, O.G.S., The Eye Goddess, Phoenix House: London 1957.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- van Hoek, M.A.M.,”Prehistoric Rock Art around Castleton Farm, Airth,” in Forth Naturalist & Historian, volume 19, 1996.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks as always to Nina Harris, Fraser & Lisa Harrick, Paul Hornby, Frank Mercer, Penny & Thea Sinclair, for their additional senses and input.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian