Chambered Cairn: OS Grid Reference – NS 00499 34665

Also Known as:

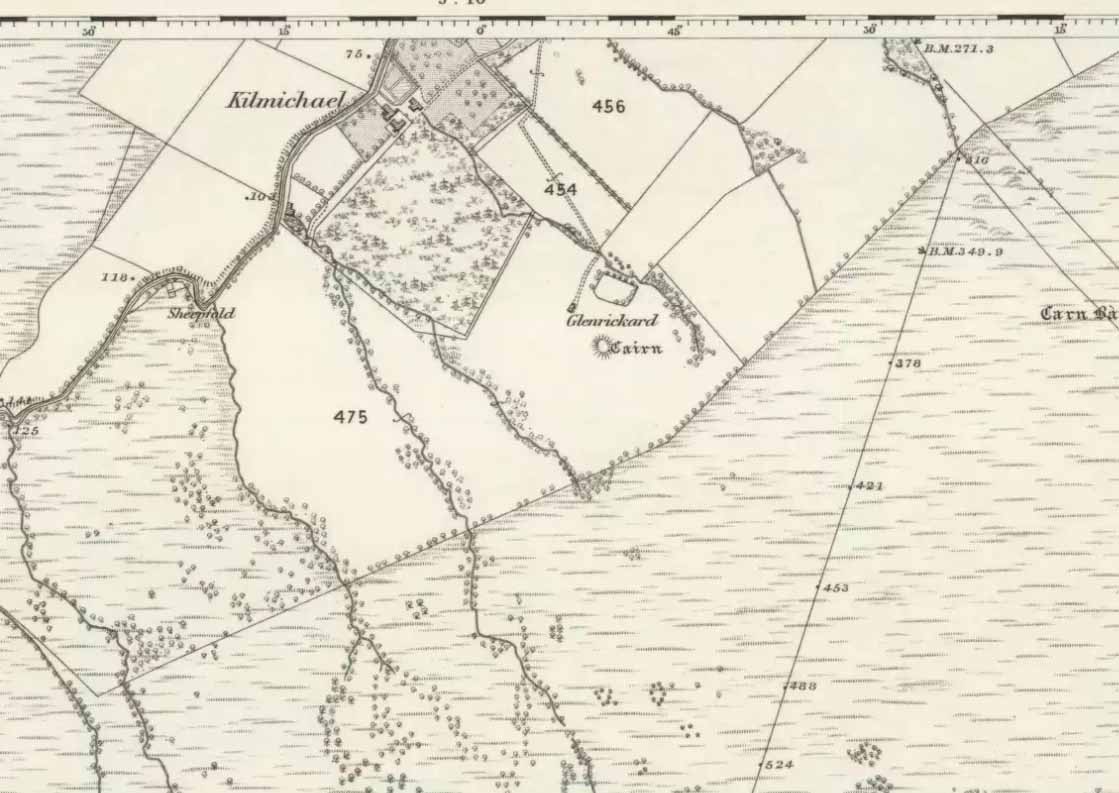

From Brodick, walk up the Glencloy dirt-track towards the friendly Kilmichael Hotel but turn off on the left shortly before hand, up another footpath, crossing the stream until you eventually reach the derelict house which was built into the edges of this old tomb. Upon the small rise above here, at the edge of the forestry commission trees, you’ll notice the overgrown ruins of the old tomb.

Archaeology & History

The remains here are somewhat overgrown and ramshackled, but I still like this place and in my younger days used to spend a lot of time here. It can get quite eerie in some conditions and seems to validate some of the folklore said of it. The site was described in Balfour’s (1910) magnum opus as:

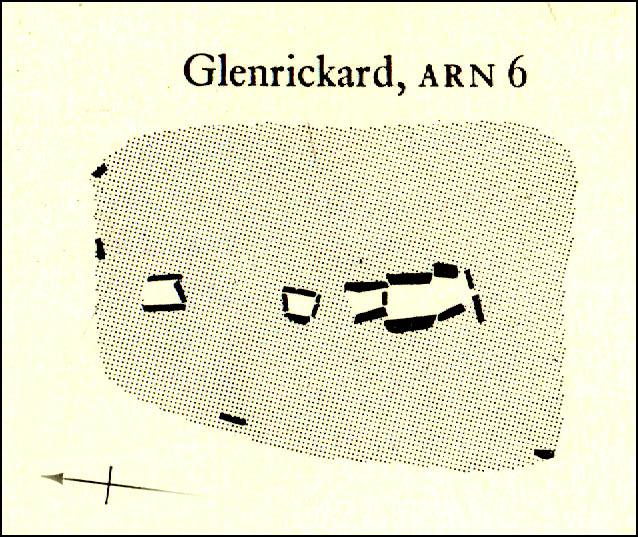

“Situated in Glen Cloy, on the moor above Kilmichael House, close to a cottage called Glenrickard. There are no traces of a cairn or of a frontal semicircle. The chamber is formed of rather light flags, with their upper edges nearly on the same level, so that the monument is more like a series of cists than a chamber. The roof and end stone have gone; there are two portal stones, but the gap between them is only 7 inches. The chamber is directed N and S, with the portal to the south. There have been three compartments, but they are rather smaller than usual, the third from the portal being only 3 feet 10 inches long by 2 feet 2 inches broad. Two feet 6 inches from this compartment is another cist, which is possibly a short cist representing a secondary interment, and 10 feet farther north is a second ruined cist placed at a different angle. This last has the appearance of a short cist, but it is not carefully constructed and differs little from the component compartments of the chamber. The structure is anomalous, and may perhaps be regarded as representing a phase of degeneration in the transitional period.”

Audrey Henshall (1972) later descried the site in greater details in her own magnum opus and told that “two rude clay urns of the primitive flower-pot pattern (were) found in the chamber”, along with “calcined bones, said to have been in the two vessels.”

Folklore

Said by local people to be haunted, the spirit of the tomb was said to have been disturbed upon the building of the derelict house below it. Ghosts of a middle-aged couple and young child have been seen in the house; whilst the spirit of the site can generate considerable fear to those who visit the place when it is ‘awake.’ To those who may visit this out-of-the-way tomb, treat the site with the utmost respect (and DON’T come here and hang a loada bloody crystals around the place in a screwy attempt to “clean” the psychic atmosphere of the place. If you’re that sort of person, don’t even go here! The spirit of the place certainly wouldn’t want you there).

References:

- Balfour, J.A., The Book of Arran: Archaeology, Arran Society: Glasgow 1910.

- Henshall, Audrey Shore, The Chambered Tombs of Scotland – volume 2, Edinburgh University Press 1972.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian