Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 53134 35850

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 24169

- Duncroisk 3 (Canmore)

Getting Here

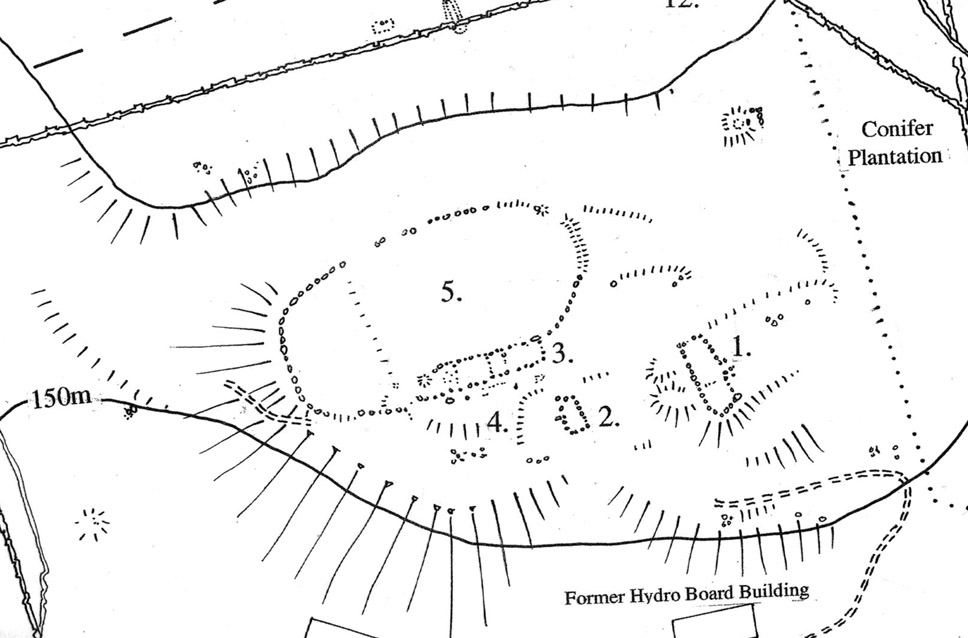

Troublesome to get to unless you’re reasonably fit. Probably the easiest route is to get to the Duncroisk 3 cup-and-ring stone. Keep walking along the riverside, climb over the first tall wooden fence and onwards till you reach the rocky crag reaching into the river Lochay. By whichever means possible, get yourself up and round this crag, but keep by the riverside till you get to the easier walkable rocky outcrop protruding into the river on the other side of the drop. Hereby, on one of the stones, look and you’ll find these faint cup-and-ring symbols.

Archaeology & History

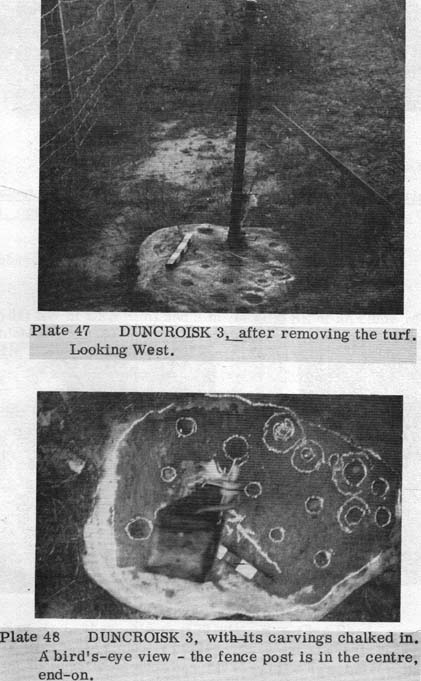

Although this carving was first described in Edward Cormack’s (1952) essay on the prehistoric carvings of the district, they have subsequently proved difficult to locate by the Royal Commission lads and other archaeologists. I’ve been here a few times looking for it and never managed to find it — until last week. When Mr Cormack first told of the design, he said:

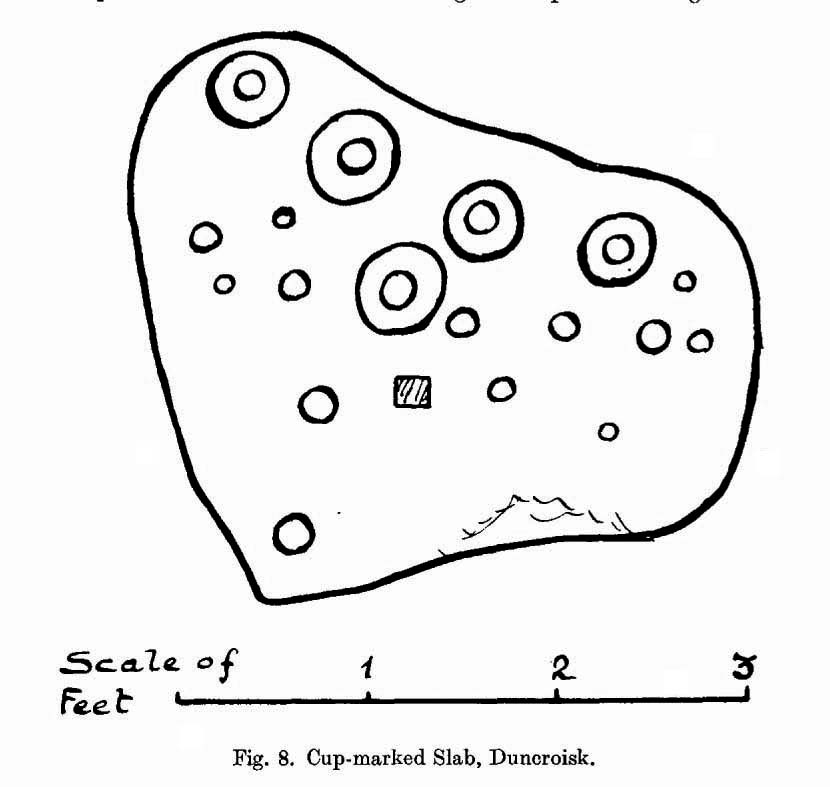

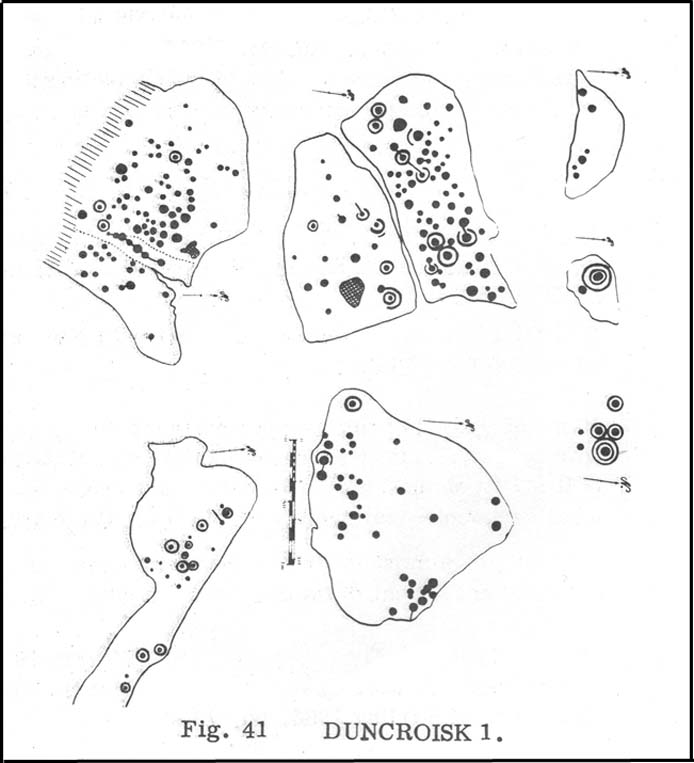

“On a smooth rock surface just above the mouth of the small burn running into the Lochay, immediately west of the cup-marked ridge, are two cup-and-ring markings a yard apart. The rings are curiously rough edged, and do not give the same impression of weathering as those on the ridge; possibly they have been silted over shortly after being cut, and exposed again relatively recently.”

A few decades later, Ron Morris (1981) came across the carving, 10 yards “southeast of an elbow of River Lochay”, as he put it. Described as “hard to find”, he went on to give a basic outline of the design as he saw them, telling there to be “2 cups-and-one-ring, both probably complete, up to 16cm (6in) diameters, with radial grooves from cup to ring—up to 1cm deep.” Or more simply, two cup-and-rings, each with a line running from the centre to the surrounding ring.

After trying to find this carving on several occasions, without success (somehow!), it was brought to my attention under the brilliant guidance of a local cat called Flambeau only last week (no lies!). In a venture down to the riverside, the great cat (in tandem with Pip the dog, who also ventures out with me to find ancient sites in this region) got to the riverside on the rock in question and began rolling about in the dust on the stone, mewing and purring away merrily! It was really brilliant to watch. Sincerely heart-warming (soz…but I can’t help it!).

I stepped over and complimented him as he looked superb (hence the photo, above) and he just kept purring. Then, curiously, he stood up and began scratching at the dried earth on the rock, mewing away whilst doing this. Twas very odd indeed. But there, exactly where Flambeau has been scratching and rolling about, it seemed a faint cup-mark was apparent. And such it was! So I got on my knees and began cleaning away the dirt from the rock — and there, right where he’d been purring and playing, was the lost cup-and-ring carving!

Its location would suggest that the carving had some relationship with water: be that the spirit of the place, or a good site where fish can be had, or a place where someone had drowned, etc. We’ll probably never know… But it’s a beautiful spot, with the impressive Stag Cottage carvings in the adjoining field, and the newly discovered Corrycharmaig East carvings on the other side of the river — plus many others in the area.

Folklore

The River Lochay where this carving is found is named after a dedication to the Black Goddess, according to Prof. W.J. Watson. (1926) The stream by the side of the carving which runs into the River Lochay has been the place where faerie music has been heard by local people in times past.

References:

- Cormack, E.A., “Cross-Markings and Cup-Markings at Duncroisk, Glen Lochay,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 84, 1952.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1979.

- Watson, W.J., The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland, Edinburgh 1926.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian