Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 6025 6558

Archaeology & History

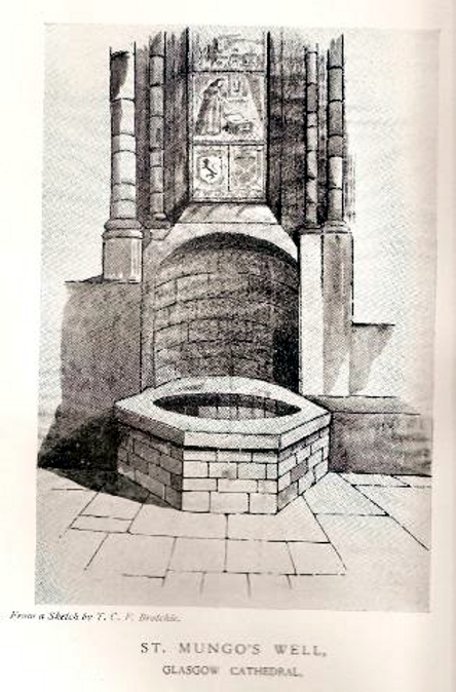

Not to be confused with the sacred well of the same name found along Gallowgate a short distance to the south, the waters of this ancient well have sadly fallen back to Earth. The structure built above it, however, is thankfully still preserved inside the Cathedral, as visitors will see.

Folklore and history accounts tell its dedication to be very early – and the tale behind the erection of the cathedral is closely associated with the waters themselves. Indeed, if the folklore is accepted, we find merely a transference of early animistic ideas about the death of an ancestor placed onto this early Saint, with a simple association in the formula of: tomb, holy site and architectural form. It could almost be Bronze Age in nature!

The lengthiest (and best) description of St Mungo’s Well was by Mr Brotchie (1920) in a lecture he gave on the city’s holy wells in April 1920, which was thankfully transcribed by the local history society. He told us:

“It seems to me that Glasgow in a very particular degree is a case that illustrates emphatically the existence of the early cult of the sacred fountain (sketch attached)… How came it to be there? In itself it represents the very beginning of Glasgow. It was to the little spring on the hillside overlooking the Molendinar that there came the earliest of christian missionaries, Ninian. All that we know of Ninian is from the account of Jocelin, the monk of Furness, who tells us that “ane holy man Ninian cam to Gleschu or Glasgow in the third century”, and made his cell on the banks of the Molendinar. When Kentigern or Mungo came to Glasgow in the sixth century, he made his settlement near a certain cemetery, which had long before been consecrated by St. Ninian, and which at the time when Jocelin wrote (twelfth century), was “encircled by a delicious density of overshadowing trees.” The crypt of the Cathedral—in reality an under church of extraordinary beauty of design and magnificence of mason work—is the shrine of St. Mungo, who is buried there, and the whole design of the lower church shows that the architect who in 1230 planned the building…built his scheme up with the idea of providing a shrine for the saint’s tomb and his holy well.

“The well is in the lower eastern corner of the church just opposite to the chapter house. John Hardying, the chronicler, who visited Scotland in 1413, states that St. Mungo’s shrine was then the centre of the life of Glasgow. In 1475 James III, on account of his great devotion to St. Kentigern, granted three stones of wax yearly for the lights at the tomb of the saint in the cathedral, near his holy well.

“St. Mungo adopted this well from the pagans of the district and changed its purpose from evil to good. Beside it he erected in 560 his little wattle hut where he died. He was buried inside it, and when the great cathedral was built the holy well was included within its walls…

“St. Mungo’s Well was a place of pilgrimage to the early christian fathers, and we find it described as “an idolatrous well” in 1614. In 1579 we have a public statute prohibiting pilgrimages to wells, and in 1629 the Privy Council denounced these pilgrimages in the strongest terms, it being declared that for the purpose of “restraining the superstitious resort of pilgrimage to chapels and wells, which is so frequent and common in this kingdom, to the great offence of God, scandall of the kirk, and disgrace of his majesties government,” that commissioners cause diligent search in “all such pairts and places where this idolatrous superstition is used, and to take and apprehend all such persons of whatever rank and qualitie whom thay sall apprehend going on pilgrimage to chapels and wells.” That decree was issued under the Dora of 1629. But all in vain. The custom of visiting chapels and wells had become a habit – and habits, as we all know, though easily formed are difficult to break. The wells continued to be visited by stealth if need be.”

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Glasgow, TNA 2017.

- Brotchie, T.C.F., “Holy Wells in and Around Glasgow,” in Old Glasgow Club Transactions, volume 4, 1920.

- Davidson, Nevile, The Cathedral Church of St. Mungo, Bell & Bain: Glasgow 1957.

- Walker, J.R., ‘”Holy Wells” in Scotland”, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume17, 1883.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian