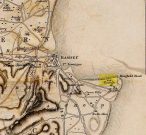

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SC 49624 91926

Also Known as:

- Chibber Maghal

- Chibbyr Vaghal

- Chibbyr y Vashtee

Archaeology & History

St. Maughold’s Well—also called Chibbyr Vaghal—is found on the northeast side of the headland on the cliff face about a hundred feet above the sea, a quarter mile from the St. Maughold’s church. It was a pilgrimage site which people visited on the dates of November 15 and July 31.

“…Beneath the head, under some moss clad rocks, is a deep spring, formerly much celebrated for its supposed medicinal virtues.”

– George Jefferson, 1840

Its medicinal properties are of great repute and was resorted to by many on account of its sanctity by crowds of pilgrims. The well was traditionally visited on the first Sunday in August, being the first Sunday after the Saint ‘s principal feast day, July 31 (significant in the Celtic calendar), but the devotions here have their origins in pre-christian times. The principal benefit at the well was a cure for sore eyes. After bathing the eyes or drinking the water it was/is customary to drop a coin, pin or button into it. Alternatively, a piece of cloth which had been used for bathing the eyes would be left by the well or on a nearby bush. As the cloth rotted, the ailment would be cured; while anyone who picked up the rags would himself receive the complaint associated with the offering; and to receive the full benefit of the well’s curative powers it should be visited on that first Sunday in August, and “while books were open in the church” — or in pre-reformation days, whilst Mass was being offered.

“…Where the spring gushes forth the rock has been hollowed into a small basin, and over it has been erected a simple shed of rough unhewn blocks of the rock immediately at hand. Hither the Saint is said to have resorted; nor is it altogether improbable that nearly fourteen hundred years ago at this very font he administered the baptismal rite. Certainly it was for many ages in great repute for its medicinal properties, and was resorted to on account of its sanctity by crowds of pilgrims from all parts. Nor is it yet forgotten.”

– J.G. Cumming, 1848“…A drink of its water, taken after resting in the saint’s chair close by, is supposed to be an unfailing cure for barrenness in women.”

– A.W. Moore, 1890

Folklore

At Maughold churchyard above the well, ghostly whispers are said to be heard by the steps in the churchyard. This is interesting as when excavations were done here, the labourers found bones buried beneath the same steps. They were dug and exposed during the day and one worker who stayed in the church heard distant sounds, whispers and murmuring all around the church. When the bones were reinterred, the haunting stopped. (Bord & Bord 1985)

References:

- Bord, Janet & Colin, Sacred Waters: Holy Wells and Water Lore in Britain and Ireland, Granada: London 1985.

- Cumming, J.G., The Isle of Man: Its History, Physical and Ecclesiastical, J. van Voorst: London 1848.

- Hall, John, “Earth Mysteries of the Isle of Man,” in Earth, no.17, 1990.

- Moore, A.W., The Surnames and Place-Names of the Isle of Man, Elliot Stock: London 1890.

- Jefferson, George, Jefferson’s Isle of Man, G. Jefferson: Douglas 1840.

- Radcliffe, William & Constance, A History of Kirk Maughold, Manx Museum: Douglas 1979.

© John Hall, 1990

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.