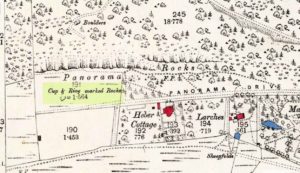

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 11467 47287

Also Known as:

- Carving no.101 (Hedges)

- Carving no.227 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Rocking Stone

Come out of Ilkley/bus train station and turn right for less than 50 yards, heading left up towards White Wells. Go up here for less than 100 yards, taking your first right and walk 300 yards up Queens Road until you reach the St. Margaret’s church on the left-hand side. On the other side of the road, surrounded by trees is a small enclosed bit with spiky railings with Panorama Stones 227, 228 and 229 all therein: the least-decorated one on the left being the one we’re dealing with here.

Archaeology & History

This is another of the caged Panorama Stones, found within the awful spiked fencing across from St. Margaret’s Church, just out of Ilkley centre. Originally located ¾-miles (1.2km) WSW of its present position in Panorama Woods (at SE 10272 46995), along with its petroglyphic compatriots in this cage, the carving was moved here in 1890 when a Dr. Little—medical officer at Ben Rhydding Hydro—bought the stones for £10 from the owner of the land at Panorama Rocks, as the area in which the stones lived was due to be vandalized and destroyed. Thankfully the said Dr Little was thoughtful and as a result of his payment he had some of the stones saved and moved into their present position.

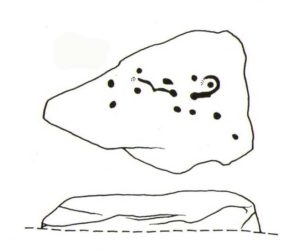

It was first described by the northern antiquarian and petroglyph pioneer, J. Romilly Allen (1879) , who saw it in the now-destroyed “rough inclosure”, as he called it, along with the other stones now in the same Ilkley ‘cage’. Its present position does it no justice whatsoever in terms of its original position. It was ostensibly a rocking stone: this seemingly trivial-looking boulder was sat on top of the much-cropped Panorama Stone 228 (a yard east of the three in this outdoor cage). Allen (1879) was fortunate enough to have seen the stone before it was uprooted, telling us how this topmost stone, “has eleven cups, wo of which are surrounded by single rings.” The modern archaeologist John Hedges (1986) told it to be in a “bad state,” with “very worn carvings, fourteen cups, one with partial ring and groove.” Its situation deteriorated further, as stated by rock art students Boughey & Vickerman (2003), who noted,

“medium-sized, roughly triangular rock, its surface recorded as in a bad state in 1986 and now (2002) even worse. Fourteen cups, one with partial ring, one groove.”

And its condition isn’t helped by its inaccessibility, when groups like the ‘Friends of Ilkley Moor’ or the local archaeologist should be at least annually cleaning this and the adjacent carvings. If they’re incapable, there are sincere people in antiquarian, history and pagan groups who would probably help out…

In truth, this carving cannot be seen in isolation, nor merely reduced to a numeric catalogue in some rock art corpus. We must contextualize its relationship with the once much-larger multiple cup-and-ring stone on which it sat and then see it as it was in the landscape. Originally of course the rocking stone was Nature’s very own creation. As humans began migrating over and eventually occupying this once-wooded arena, the rocking stone became intimately related with animistic magickal rites and, over time, petroglyphs began to be etched upon the stone. Most probably the flat underlying rock surface was carved upon first, and a symbiotic relationship was forged between Earth’s surface and the small rocking stone, both of which were used in oracular and other rites. Over centuries, as the cups and rings on the earthfast stone grew, the mythic status of this small rocking stone allowed for the encroachment of carvings, and eventually cup-marks began to be etched upon it too. Later still, as the neolithic period moved into the Bronze Age, the people began to build a low-walled stone enclosure around this and the nearby multiple-ringed carving – similar to the multi-period enclosure at Woofa Bank and other sites on these moors. It was all a very long and gradual process.

In truth, the mythic status of this once-impressive site would have been maintained—in one form or other—well into the medieval period. But that’s another matter altogether…

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Bennett, Paul, The Panorama Stones, Ilkley, TNA: Yorkshire 2012.

- Bennett, Paul, Aboriginal Rock Carvings of Ilkley and District, forthcoming.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Downer, A.C., “Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association,” in Leeds Mercury, August 28, 1884.

- Eliade, Mircea, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, Harcourt, Brace & World: New York 1959.

- Hadingham, Evan, Ancient Carvings in Britain, Souvenir Press: London 1974.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Heywood, Nathan, “The Cup and Ring Stones of the Panorama Rocks”, in Transactions Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, Manchester 1889.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to both Dr Stefan Maeder for help in cleaning up the stones; and to James Elkington for allowing use of his photos in this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian