Henge Monument: OS Grid Reference – SD 9822 8728

Also Known as:

- Castle Dyke

Go west through Aysgarth village along the A684 road and, just as you’re coming out of the town, take the left turn on the Thornton Rust road, past Town Head Farm, and turn left up the track (called Folly Lane). Go past the house where the track veers to your right and follow it straight on (don’t turn up the track on your left a short distance along). Keep walking on here for nearly a mile (about 10 mins), keeping your eyes peeled for the embanked rise in the field on your left, which is where the henge can be found! You’re damn close!

Archaeology & History

One of the earliest accounts I’ve found describing the Castle Dykes henge is in Mr Barker’s (1854) lovely literary exploration of Wensleydale, where he describes, “on Aysgarth Moor, which is now enclosed, may be seen a circular encampment, probably Danish” in origin. But he tells no more. When Edmund Bogg (c.1906) came here fifty years later, he added little extra, simply telling of, “the earthworks known as ‘Castle Dykes’, probably Angle or Danish, although Roman relics have been found here.” However, the brilliant Mr Speight (1897) gave what seems to be the earliest real description of the site when he described “the Celts” and the earliest settlers of the region, saying how:

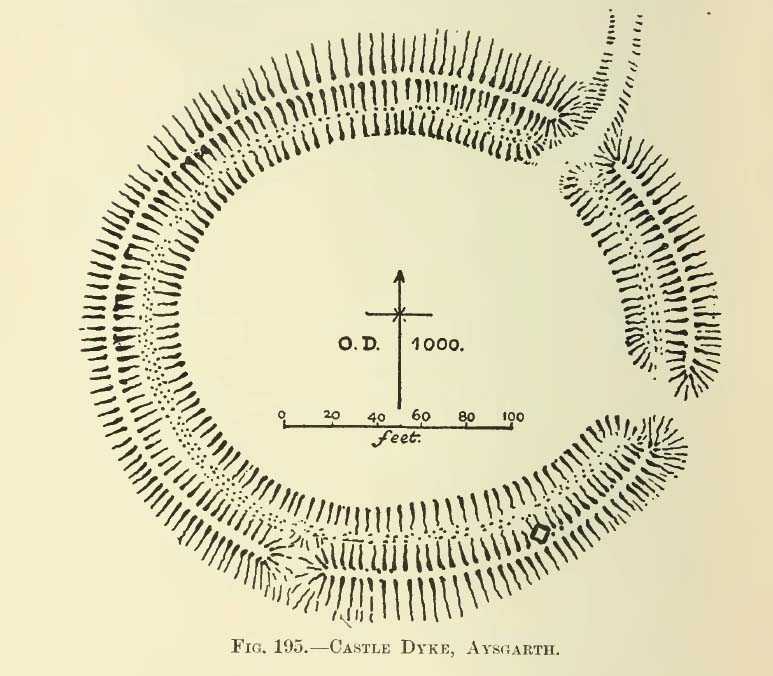

“The so-called ‘Castle Dykes’ at Aysgarth betrays a probable connection with the same settlers. It is an irregular circular rampart, measuring about forty yards across its longest diameter, and not unlike the earthwork on Harkaside called ‘Maiden Castle’… A ditch completely encloses the mound, which, it should be noted, is unusually low, being little higher than the outer bank or upcast from the trench. It is totally different from the elaborate burh at Middleham; indeed, from its low and simply form, as well as from its situation in Celtic territory, there seems little doubt that it was the work of these early people.”

Speight also made a suggestion that the place-name of Aysgarth itself may derive from this monument. He may have a point. A.H. Smith (1928) and other place-name authorities tell the name to derive from “an open space” either surrounded by, or — in some way — defined by oak trees. We might never know for sure…

Not long after the works of Speight and Bogg came the first real survey of British prehistoric earthworks by A.H. Allcroft (1908) — and amidst the mass of archaeological curiosities (as many were at the time) was another description of this great ceremonial monument. Allcroft told that here,

“a weak vallum of earth encloses a perfectly regular oval area measuring from crest to crest of the vallum 257 feet (east to west) by 217 feet (north to south). Immediately within the vallum is a broad fosse varying from 25 to 32 feet in width. The vallum at its highest (east) rises not more than seven feet above the floor of the fosse. The “island” measures 196 by 160 feet and is perfectly flat. There is no berm and no outer fosse. The vallum is broken by three gaps, of which that to the southeast is apparently original, as the fosse has never been excavated across it. The other gaps point respectively northeast and south-southwest, the latter being a mere depression like that to be seen at the eastern side of the northern ring at Thornborough. At one point in the vallum, on the southeast, a single large stone rises slightly above the turf which otherwise covers the whole work, and certain depressions observable at other points suggest that other such blocks have been removed —that, in fact, it originally had a peristalith standing upon the vallum. The principal entrance looks towards Pen Hill…”

Around the same time, the early scientific discipline of astroarchaeology was taking root and in Sir Norman Lockyer’s Nature journal, the reverend J. Griffith (1908) explored the potential astronomical orientation of Aysgarth’s Castle Dykes, thinking that the main entrance to the site gave indications of an alignment towards either Alpha Centauri or Capella. Y’ never know…

Although many visitors and local people knew of Castle Dykes, it was pretty late before the site gained status as a henge monument. This happened following a visit here by the pedantic archaeologist R.J.C. Atkinson (1951) in September of 1948. Following his visit, Atkinson described the place, saying:

“It consists of an oval enclosure bounded by a well-preserved ditch and external bank, with an entrance on the East side. Two small gaps in the bank, without corresponding causeways across the ditch, were probably made in recent times to allow the escape downhill of the surface water which collects in the ditch. The dimensions in H. Allcroft’s plan are incorrect. The markedly oval shape is probably in part dictated by the situation, in order that as much as possible of the enclosed area should lie on the level ground topping the ridge. There is no sign of any stone structure in the central area, but the district abounds in stone walls, for which the site may have been robbed in the past.”

In more recent years, archaeologists have speculated that the site was a sacred site or meeting place, aswell as a site where trade occurred, particularly a place where axes were traded; but this latter idea is more due to the projection of a modern religious notion, of ‘The Market’ with little veracity in terms of the site’s function. This increasing imposition of ‘economics’ and ‘trade’ (see Brown 2008:44-6) as vital ingredients to this and other sites has little relevance outside of a simple epiphenomenalistic adjunct to magical and tribal exchanges. But such notions are outside of archaeological frameworks, so we shouldn’t be surprised at so prevalent an error.

But this place is damn impressive — though with the exception of Mr Griffith, one notable ingredient archaeologists seem to have forgotten about was the position of this site in the landscape. The views surrounding the henge are excellent, giving a 360° arena all round. If the monument once had a ring of stones around it, as Allcroft suggested, the views would still have been the same. A modern excavation here might prove worthwhile and, as a result, open up once again, the potential for further astronomical investigations with the many hills and notches along the living horizon. This site, whilst requiring analysis of it as a ‘specimen’, must also be placed in the context of the wider living environment which, to all early traditional cultures, were such important and integral ingredients.

We have also found some previously unrecorded prehistoric remains nearby which, hopefully, we’ll be able to explore a little more in 2011 and report here.

…to be continued…

References:

- Allcroft, A. Hadrian, Earthwork of England, MacMillan: London 1908.

- Atkinson, R.J.C., “The Henge Monuments of Great Britain,” in Atkinson, Piggott & Sandars’ Excavations at Dorchester, Oxon (Department of Antiquities: Oxford 1951).

- Barker, W.G.M.J., The Three Days of Wensleydale, Charles Dolman: London 1854.

- Bogg, Edmund, Wensleydale and the Lower Vale of Yore, E. Bogg: Leeds (c.1906).

- Brown, Paul & Barbara, Prehistoric Rock Art in the Northern Dales, Tempus: Stroud 2008.

- Griffith, Rev. J., “English Earthworks and their Orientation,” in Nature, volume 80, 18 March 1909.

- Harding, A.F., Henge Monuments and Related Sites of Great Britain, BAR 175: Oxford 1987.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire,Cambridge University Press 1928.

- Speight, Harry, Romantic Richmondshire, Elliot Stock: London 1897.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Richard Stroud for use of his photo of the henge.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian