Henges: OS Grid Reference – ST 540 528

Also Known as:

- The Castles

- Priddy Circles

- The Rings

Archaeology & History

Although cited in all modern archaeology texts as a series of four henge monuments, a recent article by J. Lewis & D. Mullin (2011) inform us that these “are not henges but belong to a tradition of enclosure that predates them and had a different function.” We’ll have to wait and see what they mean by that! In the meantime, we’ll have a quick scurry through the historical accounts of these four impressive ‘henges’ as Burl, Piggott and the others call ’em.

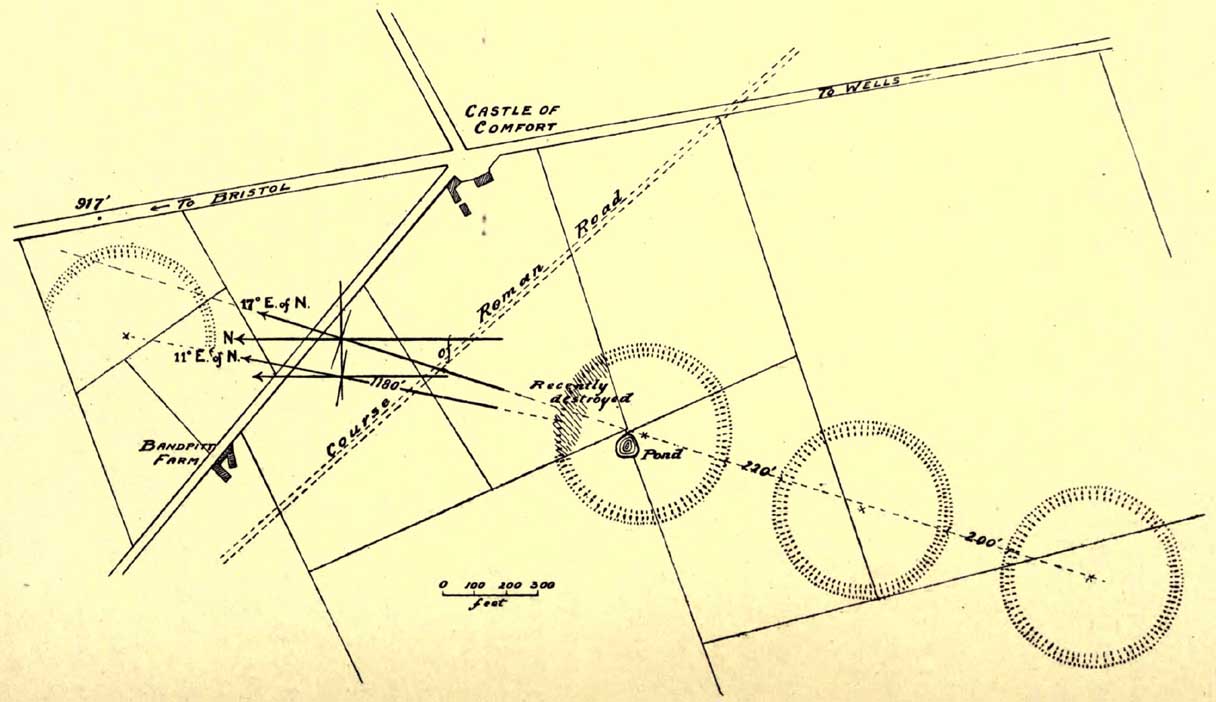

Surrounded at all angles by numerous barrows and tumuli, these four great henge monuments were shown on the 1887 Ordnance Survey map as a row of ‘Supposed Ring Forts’, when such ideas were in vogue, running in a line roughly SSW-NNE; the third one up having a couple of ponds within it. A brief early account of them was given by Harry Scarth (1859)—who was describing the series of nine round barrows a few hundred yards to the south—who told them to be “circular banks” each 500 feet across. The first more detailed account was in A.H. Allcroft’s (1908) classic text, where he wrote the following:

“…Close to the Castle of Comfort Inn, where the high road to Bristol crosses the line of the old Roman road running north-westward towards Charterhouse, there lies immediately west of the high road a series of four circles…all of one size, all of one plan, and all as mathematically exact as circles could well be when executed in such a soil and on such a scale. Although they have suffered greatly from the mining operations which have scarred all the Mendips, as well as from the plough — one of the four is almost obliterated — they are still quite easy to make out. The diameter of each is some 550 feet within the area, which is surrounded by a broad low vallum, and that again by a correspondingly broad and shallow ditch. The height of the vallum above the ditch, where best observable, is some 5 feet. There are no determinable entrances. The most southerly of the group is about 250 feet away from the second ; the second about 200 feet away from the third; and a line joining the centres of the first and third passes through the centre of the second also, and points 17° east of north. The fourth circle lies 1,200 feet away from the third, not in a right line with the others, but slightly to the west. Between the third and fourth circles passes the Roman road. Within the third circle is an old pond of some size.

“With every appearance of being all of one date, and that a venerable one, these circles lack every characteristic of military works. Their peculiar disposition, their painstaking regularity, and their identity of size, all suggest that they must, if really old, be of ritual, and perhaps of astronomical character”

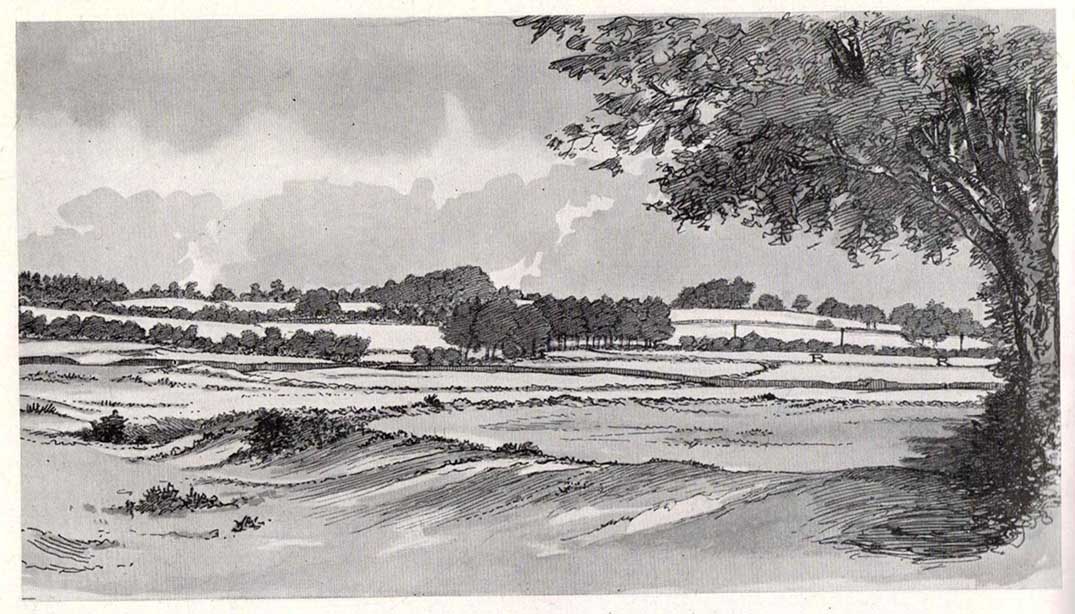

Allcroft’s ideas of ritual and astronomy were pretty good for the period, as we take it for granted these days that such events occurred at henges — so the existence of four such sites right next to each other, would have made this one helluva place in neolithic and Bronze Age periods. A few years after Allcroft, the henges were described in Mr Burrow’s (1924) excellent illustrated survey, from which the drawing of the two central henges is taken (the two ‘R’s in the background highlight the line of the Roman road which runs past them). Burrow’s didn’t add much more of any note, simply telling:

“…in the fields north and south, are placed earth-work rings, each about 180 yards in diameter, on a line placed slightly north by east. The most northerly of these rings is almost obliterated, but the three on the west of the road from Chew Stoke to Oakhill are quite clearly defined, as my drawing (above) will show. I have been able to include two of these remarkable rings in my picture, the edge of the bank (which was, when I saw it, fringed with yellow gorse), being about 6 feet above the level of the ditch outside. It is generally supposed that these ringed earthworks were connected with some prehistoric ritual, and Hadrian Allcroft thinks were used for primitive astronomical observations or the construction of a primitive calendar.”

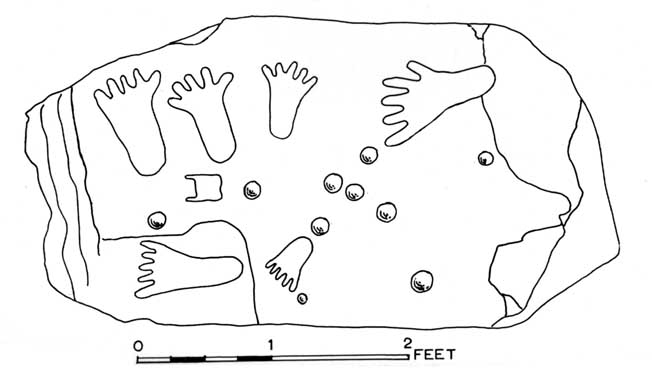

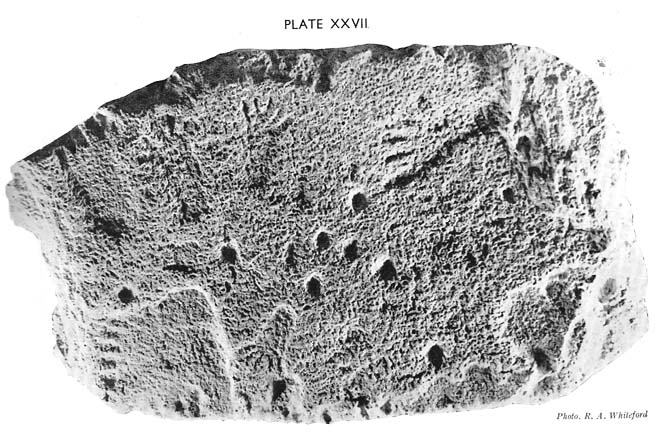

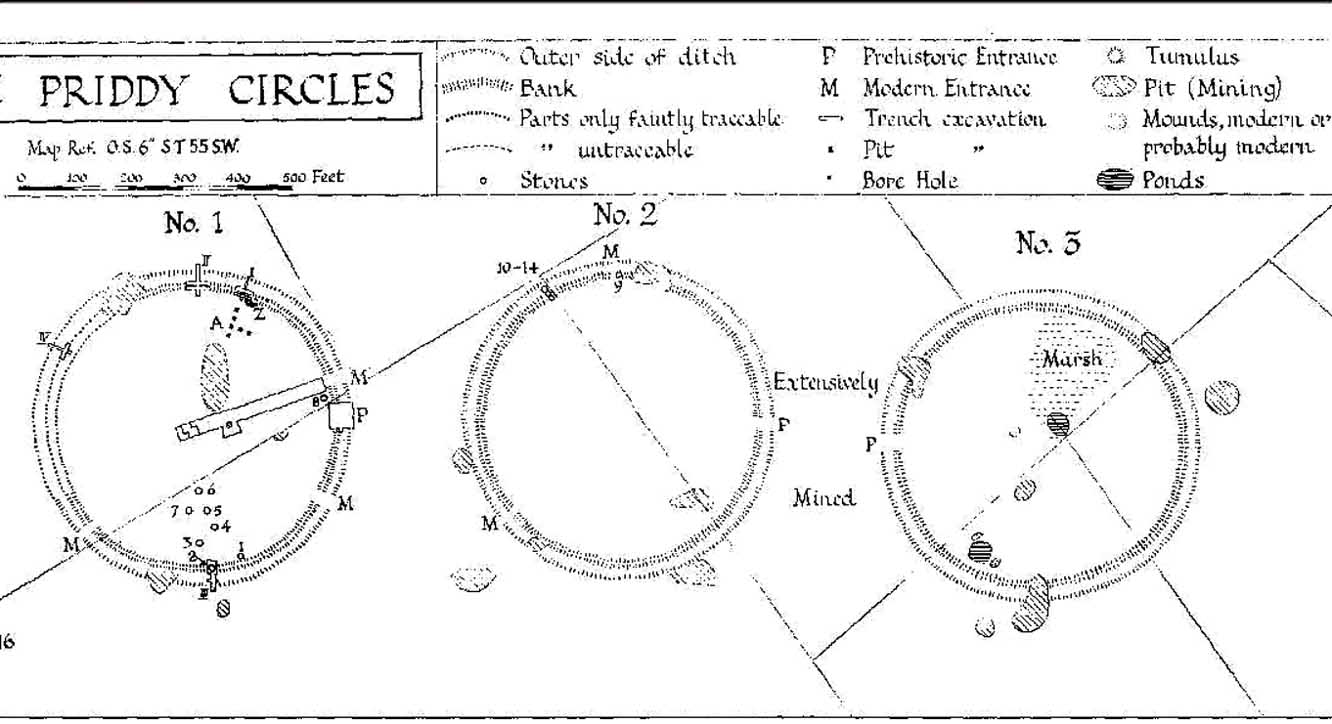

Many years later when archaeologist K.S. Painter (1964) came to describe these henges, he listed them as “stone circles” (what the hell was he on!?), but this error may derive from the finding of several stones that once existed inside the southernmost Henge 1. These were uncovered following excavation work done here by E.K. Tratman (1967) and his colleagues, who explored and numbered the four henges—running from south to north—as follows:

“Circle 1: This is tolerably complete. A portion of the southwest quadrant has been destroyed by mining and there are three modern gaps in the ring. Mining has involved the ditch on the west and south, and to a small extent on the east. There is an irregular extensive hollow west of the centre and this too is a product of mining and contains a number of large stones so derived. The circle is not quite a true one, being flattened slightly on the west. The circle has a diameter from bank top to bank top of 520ft. The single original entrance is NNE of the centre. Stones 1 and 3-7 were removed by the farmer before excavation, but subsequent ploughing immediately after removal did not reveal any change in soil texture or colour. Stone 8 was placed in its present position quite recently. It is not known where it came from. Other stones have recently been placed on top of the bank east of the entrance by the farmer (1964-5). Stone 2 is in a relatively ancient position.

Circle 2: This is a true circle and its diameter and position of its entrance are similar to Circle 1. It has been considerably disturbed by mining. A group of stones (10-14) and stone 9 represent modern collections from the field. None of them is in its original position. There are two modern gaps in the ring.

Circle 3: This is distinctly flattened on the east and west. The N-S diameter is 520ft and the E-W 490ft from bank top to bank top. The northeast quadrant reported by Allcroft as being levelled is still traceable. The circle has been greatly disturbed by mining… The entrance is SSW of the centre, the opposite pole to circle 1 & 2, and has probably been widened, perhaps by miners. The marsh may be an original feature or the product of mining. The two ponds are certainly modern, and so is a small mound, which is probably spoil from the major pond.

Circle 4: This is incomplete. It has a diameter of 560ft, which is considerably larger than any of the others. The OS map shows only the eastern semi-circle remaining. However, the bank and in part the ditch can be traced…If the visible and proved end of the ditch on the SSW was intended to be at the edge of the causeway, then the entrance would have been in the same position as that of Circle 3.”

Very recently, a local land-owner quite deliberately bulldozed a large portion of the southern henge in this complex, destroying much of it. This act of criminal vandalism will hopefully not go unpunished and is, at the present time, going through the courts.

…to be continued…

References:

- Allcroft, A. Hadrian, Earthwork of England, MacMillan: London 1908.

- Burl, Aubrey, Prehistoric Henges, Shire: Princes Risborough 1997.

- Burrow, Edward J., Ancient Earthworks and Camps of Somerset, E.J. Burrow: Cheltenham 1924.

- Lewis, J. & Mullin, D., “New Excavations at Priddy Circle 1, Mendip Hills, Somerset,” in Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society, volume 25, 2011.

- Painter, K.S., The Severn Basin, Cory, Adams & Mackay: London 1964.

- Scarth, Harry M., “Some Account of the Investigation of Barrows on the Line of the Roman Road Between Old Sarum and the Port at the Mouth of the River Axe,” in The Archaeological Journal, volume 16, 1859.

- Tratman, E.K., “The Priddy Circles, Mendip, Somerset,” in Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society, volume 11, 1967.

- Wainwright, Geoffrey J., “A Review of Henge Monuments in the Light of Recent Research,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 35, 1969.

Acknowledgements: – To Pete Glastonbury, for use of his aerial photos of the site. Huge thanks Pete!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian